Condition

A Fascinating Yet Flawed Oddity

In the vast world of unusual ammunition, strange and unusual peaks my interest. The .357 Magnum multiball loading is one such case. One that sent me digging deeper into the history of the concept.

At first glance, the concept of firing multiple projectiles from one revolver round might sound brilliant—two projectiles for the price of one trigger pull!

Yet, in practice, “multiball” or “duplex” ammunition has repeatedly stumbled against obstacles in everything from accuracy to real-world effectiveness. Below, we’ll explore the strange history of these multi-projectile loadings, spotlight the .357 Magnum multiball round Remington briefly offered, and discuss how modern takes on the idea still struggle to outshine more traditional single-bullet loads.

Table of Contents

Multiball Cartridge History

Origins of Multiball: Early Experiments (1879 to 1903)

Before we dive into the

The dream of firing multiple projectiles from a single chamber dates back well over a century. On June 4, 1879, an experimental “multiball” loading was tested by the U.S. Army. According to the official “Report of the Chief of Ordnance” submitted by Captain John E. Greer, this new multi-projectile round exhibited dismal accuracy beyond short distances and lacked sufficient penetration.

Cross section diagram from the 1879 Report

It also weighed more than single-bullet cartridges and threatened to require modifications to the Colt revolvers of that era. As a result, the concept was scrapped almost as soon as it appeared.

Even then, you can see the recurring issues: heavier weight to transport, poor grouping, and minimal improvements in hit probability—if any. Future experiments would struggle to resolve these concerns.

In 1903 another multiball loading was created for the 45-70 Govt cartridge that consisted of three lead ball rounds in a standard 45-70 Govt cartridge. The cartridge, manufactured by Frankford Arsenal was another attempt to revive the idea. One that would continue on into the modern day in various forms.

The 45-70 multiball loading from 1903 – Image via Ammo One

SALVO & Duplex: The Mid-Century Revival

Fast-forward to the 1950s, and we arrive at the Army’s SALVO and SALVO II programs, quickly followed by the Special Purpose Individual Weapon (SPIW) project. Among the many wild ideas tested—like flechette cartridges—were .22-06 duplex, triplex, and even possibly quad-stack rounds. The premise, once again, was that multiple smaller projectiles would increase hit probability by up to 65%. On paper, it seemed ingenious.

However, subsequent trials revealed that fancy math didn’t always translate to battlefield utility. Although the .22-06 duplex managed to put more lead in the air, real-world tests found no clear tactical edge over proven single-bullet designs. Munitions featuring numerous pellets or short bullet segments might pattern effectively at point-blank ranges, but beyond that, accuracy deteriorated sharply.

A 1960s Twist: Colonel Askins & Triple .38

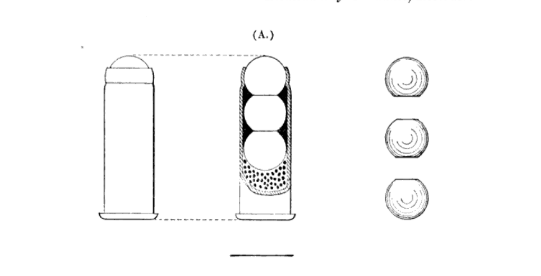

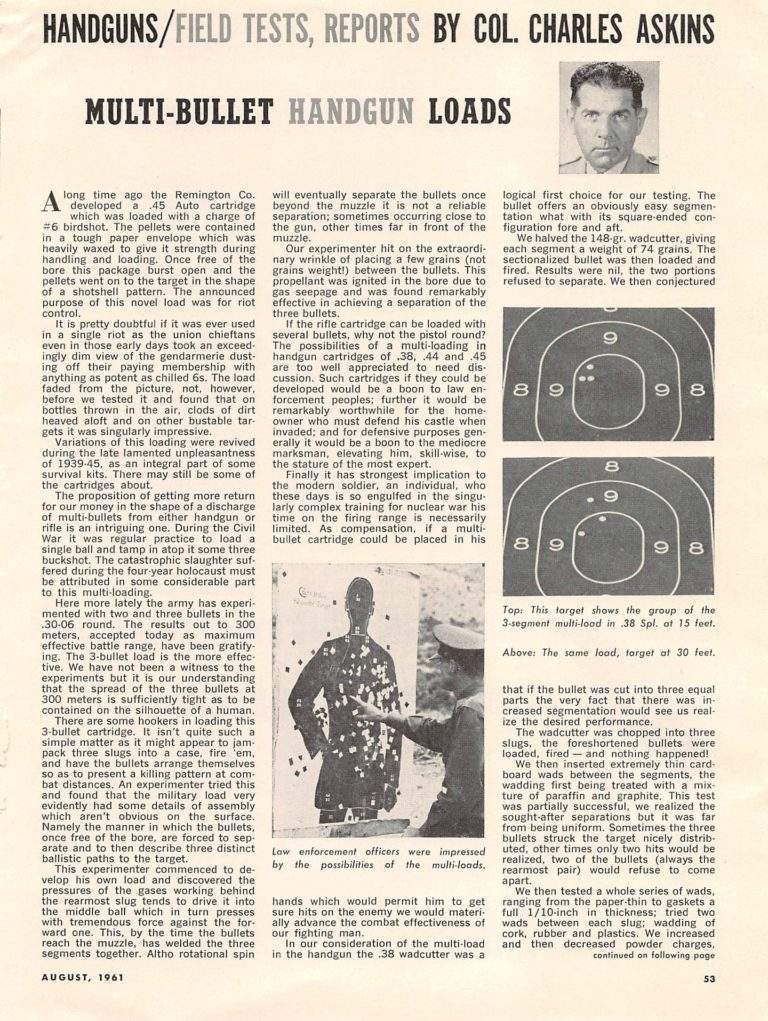

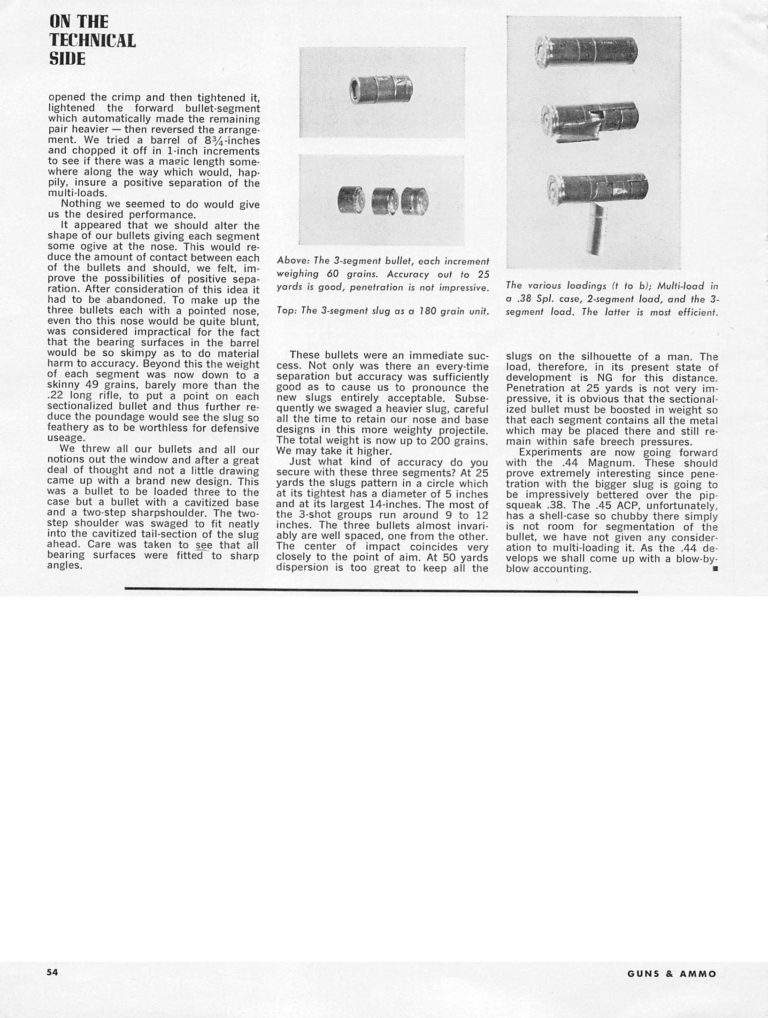

In 1961, noted gun writer Colonel Charles Askins reported on an experimental .38 Special round that featured a wadcutter cut into three 60-grain segments—an idea he notes that had been tried off and on previously.

Test-fired at up to 25 yards, accuracy was, surprisingly, decent, but penetration proved inadequate. Though interesting, the triple-wadcutter never moved beyond the realm of a fun range trick.

In these accounts, a common refrain emerges: multiball ammunition typically performed no better than conventional rounds in real-world or duty scenarios. Penetration was often lackluster, and consistent grouping remained an elusive goal. A scan of the article can be seen below. (Shout out to IAA forum member selsnslim for posting this)

Enter the .357 Magnum Multiball Round (1989–1994)

Despite the early failures, the promise of multi-projectile loads never truly disappeared. By the late 1980s, Remington rolled out the .357 Multiball round—one of the boldest attempts yet to bring multi-bullet ammunition to market. Cataloged from 1989 to 1994, this specialized .357 Magnum load crammed two 70-grain 000 buckshot pellets into a single case. The result was a combined projectile weight of roughly 140 grains—well within normal .357 Magnum specs in terms of velocity and pressure.

Remington’s aim was to give law enforcement an alternative load with potentially greater lethality or improved chances of hitting a target under stress. Yet, the .357 Multiball garnered only niche interest among police and quickly vanished from mainstream distribution.

The Sticking-Together Problem

Interestingly, in tests at LAIR, PSF, San Francisco and personal accounts suggest that the two pellets in .357 Multiball often left the muzzle still partially locked together. Instead of spreading out in flight, they’d essentially behave as a single projectile—negating the entire point of a “scatter shot” from a revolver. Where they did separate, the resulting patterns weren’t especially tight, and neither pellet carried the momentum of a single bullet, limiting penetration.

In short, “two pellets, one shot” rarely behaves as intended.

Terminal Performance Woes

Since each pellet weighed just 70 grains, each lacked the penetration typical of a standard 125- to 158-grain .357 slug. Early testers saw limited expansion and modest energy transfer, especially beyond very short distances.

These results offered no tangible improvement over typical jacketed hollow points. Realistically, it’s no wonder the line was discontinued by the mid-1990s. While I can’t find much hard information on the .357 Magnum multiball loading that is the center of the discussion, some claimed numbers for energy were 210 Joule at the muzzle for the .38 Special version and 550 Joule for the .357 Magnum loading.

Broader Tales of Multiball: Modern Takes

Even though Remington’s .357 Multiball ended, the concept pops up from time to time. For instance, Double Tap Ammunition introduced an “Equalizer” line that stacks a hollow point in front of a smaller disc with a gas check. Their product range extends from 9mm +P all the way to .44 Magnum, .454 Casull, and even .500 S&W Magnum. We see the same design logic: a two-in-one approach that hopes to double the stopping power. You can see their first party ballistics testing in the video below. The results show that it is on par with other defensive hollow point loads.

Another, and maybe more familiar take on the multiball concept is the idea of pistol or small caliber rifle rounds with shot in them. CCI has maintained a “snake shot” load in various pistol calibers and .22 caliber loadings. This forgoes any attempt at being a defensive round and squarely targets pest and snake control.

Why Multiball Keeps Failing to Gain Ground

The .357 Magnum multiball loading was far from the first to try and fail at this concept. Looking over some of the various attempts we can see an emerging pattern.

1. Accuracy Concerns: Outside of “arm’s length”, multi-projectiles seldom maintain good grouping. Severely limiting your ability to transition to targets at range.

2. Poor Penetration: Lighter bullet weights limit deeper wound channels, especially on tough targets. Though modern takes try to address this.

3. Single-Bullet Efficiency: Modern jacketed hollow points and bonded-core projectiles already yield high efficacy and reliability.

4. Cost-Benefit Analysis: Ammunition R&D is expensive, and widespread production of quirky designs lacks commercial payoff unless there’s a clear advantage.

Coupled with repeated historical letdowns—from 1879’s revolver test to the SALVO trials to Colonel Askins’s .38 and eventually the .357 Magnum Multiball—these factors have prevented multiball from displacing standard single-projectile ammo. It is possible that things could change in the future, however for militaries, simple machine pistols, PDW’s, and full auto capable carbines seem to fill cover current needs.

Conclusion - Policing the Brass

Though the .357 Magnum Multiball load once promised a radical alternative for law enforcement and self-defense, it couldn’t surmount the challenges of multi-projectile accuracy and reliable penetration. Far from a new idea, “duplex” and “triplex” rounds have surfaced time and again since at least the late 1800s—only to vanish under more rigorous testing. While modern specialty offerings like Double Tap’s Equalizer still flirt with the dream of “twice the bullet,” real-world evidence consistently shows single projectile designs—particularly well-developed hollow points—remain superior for most applications.

Curiosity aside, the .357 Multiball serves as a cautionary tale: just because you can put two or three bullets into one case doesn’t mean they’ll outperform a solitary, properly engineered round. As such, most shooters continue to trust standard .357 Magnum ammunition for critical tasks, leaving multiball loads an interesting but ultimately limited footnote in the ever-evolving story of handgun cartridges.